Chunhuhub is one of those sites that like Xkipche, is good at getting my attention, although I don’t know how or why. I just look at photos and think, “Yes, this is something I’d really like to work on” although in fact notable structures at both Chunhuhub and Xkipche strike me as being rather spartan or even somewhat nondescript in their design.

One of the structures at Chunhuhub, illustrated by Frederick Catherwood.

Both sites have also left me somewhat puzzled in terms of definitive answers, although some general things can be gleaned from them, even that Xkipche is an excellent place to start looking for the occurrence of the Egyptian Royal Cubit in ancient America.

Ancient American metrology often looks to me like the same undocumented “hodge-podge” of different units that we can see in “Old World” architecture, but at Xkipche the Royal Cubit seems to become rather monopolistic as if someone had a particular fondness for it, or found it particularly useful in making astonomical statements.

According to Andrews, John Lloyd Stephens was the first to report on Chunhuhub. Later, Teobert Maler reported on the site, describing three “castillos”, the third of which is also known as Xpostanil. Andrews has provided us with some data for both sites, and Maler has provided additional data which might be reconciled with Andrews’ data in order to serve to complement it.

Maler’s data for the “Main Palace” and “Adjacent Palace” describes distances from ends of rooms to doorways, a data point rarely if ever seen in Andrews’ assessments, so little is known about how ancient Americans made use of these architectural parameters.

https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/14054?show=full

What have I been able to glean thus far from the data? For what it’s worth, seemingly that Chunhuhub and (and Xkipche) may not be as spartan mathematically as they may be architecturally. Part of that impression comes from having doorway data that I’m still finding more or less incomprehensible – always a possible sign of an architect with a impressive command of mathematics that acccomodates a flair for unusual numbers – and also part of that impression in the observation that there may be unusual skill with squares and square roots in evidence.

This, unfortunately, may make Chunhunhub rather rewarding to work on, but also that much more of a challenge.

In terms of possible themes, what leaps out so far is the predictable preoccupation with Venus and the Moon – nothing quite as far from the usual that it might teach us the right way to represent Mars or Mercury though architectural proportion.

Interestingly, there are traces of what we might ordinarily think of as Stonehenge math. (I am fond of saying that we can often look to ancient architecture that is nowhere near our area of interesting to learn more about the architecture we are most interested in). That in itself isn’t unusual, but some of the particular references are surprising.

There are hints of the “Aubrey Number”, which also appeared in the preliminaries assessing Oxkintok in preceding posts, along with hints of the Remen, the Megalithic Foot, and the Hashimi Cubit – numbers that are virtually huge at Stonehenge. The biggest surprise so far is that there also seems to be the appearance of numbers that were previously specific to the Stonehenge “Oval with corners”, and the apparent recurrence of a number that may have been previously specific to Callanish and to the Great Pyramid.

In recent work including Chunhuhub, I also seem to be seeing what look like references to a number that has previously been associated only with the circular Cuicuilco pyramid. It’s constructed from fairly obvious metrological or astronomical elements, and can be generated as Royal Cubit in Inches / Hashimi Cubit in feet: 20.62648062 / 1.067438159 = 1.932334950 x 10.

I think it is understood that this number must have astronomical significance, although what significance exactly may still not be well understood. I might also note that 8 times this number, 1.932334950 x 8 = 15.45867960, may also be making appearances at Oxkintok and Chuhuhub for reasons I do not yet understand.

One observation that I can make in the meantime is that 5 / 1.932334950 = 3.234428896, while 3234.428896 does still continue to come back from mathematical probes as a possible value for representing the 3233 day Apsidal Precession cycle. Thus at Oxkintok, it would be more discussion of an established theme, whereas its role at Chunhuhub may be somewhat distinct from that.

The question has yet to be properly explored, but something I have in my notes may hint at a possible theme of Chunhuhub’s architecture might be the Tropical / Sidereal Month (in common calendar terms either one might be represented as 273 / 10).

354 x 273 = 193284 / 2

3233 / 273 = 11.84249084, implying that perhaps someone was making a note that 12 Pi^2 / 10 = 11.84352528 could be used to link the Apsidal and Sidereal Cycles, just as it can be used to link the Calendar Round and the Venus Orbital Period. The later formula, which is now used in my tables, is something I learned while experimenting with architectural proportions in Andrews’ data from Rio Bec.

Regarding Stonehenge, while the Aubrey Number is seen with unusual frequency seemingly everywhere, in the context of Oxkintok, it may have been mean to communicate that we can see the Aubrey Number in the inverted form proposed to be represented by Thom’s data, as essentially Anomalistic Month x Apsidal Precession Cycle.

The Aubrey Number itself, 224.4305459, has always been somewhat puzzling. I wondered what it was doing at Stonehenge – it would make a poor approximation of the Venus Orbital Period and Stonehenge is already steeped in a much better one in the form of Petrie’s Stonehenge Unit.

What I didn’t realize at the time as that the Maya may not have been the only ones to sometimes blunt the Solar Year down to 364 days, and after the recent work with Mayan calendar tables, ultimately also sometimes blunt the Venus Orbital Period down to 224. Thus the current expectation is that while the Aubrey Number may be a poor representation of the ~225 day Venus Orbital Period, it could yet end up being one of the better and more useful approximations of a 224 day Venus Orbital Period.

Just as the 56 and purportedly also 52 Aubrey Holes may give evidence that a 364 day year recognized at Stonehenge along with ample observation of a ~365 day year, they may also give indication of a 224 day Venus Orbital Period also having been observed by the architects – note that 224 / 4 = 56.

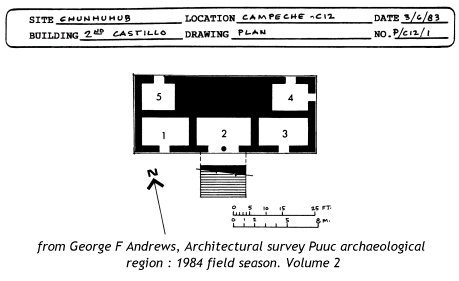

Structure 1 of the “second castillo” of Maler has some interesting things happening mathematically.

One of them is that it breaks from an emphatic pattern of room width of 2.66 m to 2.59 m = 8.4973753238 in room 4, apparently to express 1.177245771 in inverted (reciprocal form).

1 / 8.4973753238 = 1.176833977 / 10.

As I often say, 1.177245771 is one of those numbers that ALL ancient architecture seems to aspire to embodying, and with good reason, but if there is some special relevance of this number to any themes seen in the architecture of Chuhuhub, I couldn’t tell you. We may at present still be seeing less than half the available picture, and less than that overall because of the state of some of the architecture. Relatively little data is on room heights is available, often owing to structural collapse.

In the case of Room 2 of Structure 1 of the “second castillo”, we are given a height of 2.21 m = 7.250566168 ft, and 7.250566168 x 2 = 14.50113234, so this is again very close to a particular set of numbers from Stonehenge.

One way to obtain such numbers at Stonehenge is to simly convert the outer circumference of the sarcen circle into Petrie Stonehenge Units

(120 x 2.720174976) / 224.8373808 = 1.451809285

However, at Stonehenge numbers (proportions) seem to have been chosen so that some of the equations are variable and able to provide us with a remarkable approximation of the Draconic Month as a form of Megalithic Yard amid impressive interactions with the two main linear forms of the Megalithic Yard (“AEMY” and “IMY”, which I have written about extensively).

We seem to see the same thing again in room 1 of Structure E3-6 at Chunhunhub, where the length x width product in feet is 4.92 m x 2.74 m = 1.614173288 ft x 8.989501312 ft = 14.51062389.

2.74 m = 8.989501312 ft isn’t uncommon in Mayan architecture – it appears repdatedly in Andrews’ data for Uxmal, Rio Bec, Palenque, and etc – and not surprisingly since it’s a fairly obvious permutation of the Venus Orbital Period:

8.989501312 / 4 = 224.7375328, textbook value about 224.701 days.

We presume the perfected and universal form in use here is likely 2.248373808 x 4, 224.8373808 inches as the Petrie Unit and Venus Orbital Period already having demonstrated vast usefulness at Stonehenge and at Giza as well as in ancient America.

As already stated, these ancients American sites may be showing us that the Aubrey Number may be related to representation of the product of the Anomalistic Month and the Apsidal Precession cycle, and at the same time I have suggested that there may be hints of the Tropical / Sidereal Month being referenced as well.

Aubrey Number 224.4305459 = ~224.4; 224.4 / 273 = 8.219780220 = (1 / 1.216577540) x 10, looking rather like the usual Remen of 1.216733603 ft in inverse (reciprocal) form, which is also a simple division of a Solar Year of ~365 days.

224 / 273 = (1 / 1.21875) x 10, which looks more like the “Thoth Remen”, which I have suggested is an alternative form of Remen that the ancient Egyptians may have used on very rare occasions, including the Great Pyramid slopes.

Values in this range tend to be very near to 360 / Lunar Month — 360 / 29.53 = 12.19099221. When I began to see figures like this working with Mayan architecture is when I first wondered if the ancients hadn’t come up with better approximations for this than I’d generally been experimenting with, and of course it turns out that they apparently did.

I won’t attempt to try to sort out yet which they were using here, but the general message is obvious, and as just shown, values like this can be derived from 224 paired with 273 as well, lending more credence to the idea of an alternate ancient Venus Orbital Period of ~224, to complement the 225 value in prevalent use.

Interestingly, Maler’s data for E3-6 Room 3 shows distances from the ends of the rooms to the doorway of 2.86 and 2.35 m, the ratio between the two being 2.86 x 2.35 = 1.217021277.

For Room 2, if I take Maler’s distance from the end wall to door, and Andrew’s value for the door width of 1.71 m rather than Maler’s 1.68 m, 1.92 / 1.71 = ~1/2 of the Aubrey Number / 10^n.

My notes on Andrews’ data from Xpostanil (Maler’s “third castillo) show a few things that might be worth mentioning, including that sqrt 60 seems to make an appearance, as do 4 x Venus Orbital Period again, a possible approximation of the Mercury Orbital Period, what appears to likely be the double square of the Solar Year (researcher DUNE @ GHMB has recently reported this in the arrangement of pyramids at Dahshur in Egypt), blatant simple fractions of the Eclipse Year (1/2 in Room 2 and 1/4 in Room 9), along with more of the 2.66 m figure which might represent the reciprocal of the double Radian if not a similar astronomical figure obtained from Tikal.

In fact, they may have done a particularly nice job selecting numbers here, because we may see the Eclipse Year here both in the ratio and the product of Room 9

length and width 3.41 m by 2.36 m = 11.18766404 ft by 7.742782152 (probably sqrt 60); 11.18766404 / 7.742782152 = ratio = 1.444915254 = 346.7796610 / 24; 11.18766404 x 7.742782152 = 86.62364545= 346.4945818 / 4.

Perhaps then it will turn out that at Chunhuhub a special importance was placed on the Eclipse Year in general.

11.18766404 may represent 1.117818626 (1.067438159 x ((Pi/3)^2) while researchers with more orthodox inclinations might take it to be 1/10th of the square root of 125, or sqrt 5 / 2.

We also see another likely instance of the Cuicuilco number as the length / width ratio of Room 3 of the same structure. 5.18 m / 2.68 m = 1.932835821, the “perfected” version I have being 1.932334950, again the ratio between the Royal Cubit in inches / the Hashimi Cubit in feet.

That many clues gives us many questions we ask about why these particular numbers might have been deliberately grouped together, although a few have already been at least partially answered.

I could go on but I think I will leave it at that for now, it leaves me with much more to consider now if I choose to dig deeper into the mathematics of Chunhunhub here and now.

Cheers!

–Luke Piwalker