Alan Green

Many thanks to seanoffshotgun at GHMB who posted links to some of Alan Green’s videos on YouTube. I haven’t looked at the one on the Fine Structure Constant yet – that could be stretching the limits of ancient technology a bit and I have (probably sordid) tales to tell about Michael Morton’s explorations of the Fine Structure Constant – but I was quite impressed with Green’s video on the Great Pyramid and the constants contained therein.

I do things a little bit differently when it comes to accuracy, but it can be difficult to argue with a researcher who is true to their own standards of accuracy, as Green generally appears to be. In terms of allowances for accuracy, Green often seems to be in the same range of tolerances that is allowed in my own work when it’s forced on us by actions like addition and subtraction.

Probably the most notable thing to arise from my encounter with Green’s video is his manner of tracing circuits through the pyramid. Some of the researchers at GHMB have been doing interesting things with methods like these, but Green seems as if to have taken matters to a higher level – and remarkably, while things are still only in the preliminary stages, I’ve been getting some very striking results trying out some of his methods on my models – not only on the Great Pyramid, but now all three of Giza’s main pyramids.

Pyramid of Dreams

Looking for a good book to curl up with, I purchased a copy of Ric Hajovsky’s Chichen Itza: If we build it, they will come: The story of the rebuilding of Chichen Itza as a tourist attraction in the 1920s and 1930s.

I haven’t actually read it yet, but I’ve been looking at the pictures – which sounds like a horrible thing to say, but it’s actually one of the things that makes this book such a treasure is that it is loaded with rare historical photographs that allow us to trace the evolution of what we think of as Chichen Itza, with our own eyes.

Ric is the author of an excellent article that serves as a wake-up call concerning dabbling in what we’re told is the design of the El Castillo pyramid – easily enough to discourage passing on the idea of “91 steps per side” that may be nothing more than modern myth. In fact, there are passages in the book that spell out the problem with the stair counts even more emphatically (page 43).

In a way, the timing is fortunate – in the comedy of errors engendered by an El Castillo pyramid that is “made up” for tourists, if I hadn’t spent awhile believing the hype, I might never have made it onto the right path, although in the long run that is what may be particularly deceptive about the model of El Castillo as most of us think of it – that it can put us on the right path in completely the wrong way, and have us all busy making fools of ourselves in front of more learned peers if we try to make any genuinely academic efforts.

I suppose it’s a bit like training wheels on a bicycle – these modern myths can help us learn to ride the bicycle, but once we do, the training wheels may need to come off before they start causing accidents.

I have touched on this subject previously, and showed how there may still be an important astronomical and calendar related model for El Castillo and the step counts using Maler’s data (still the only data I really trust for Chichen Itza, although sadly apparently little of the site and its major structures were accessible to him at the time of his stay there), and the metrological work based on Maler’s data indicating El Castillo as a true “calendar pyramid” still stands up.

My biggest motivation for buying the book was to see if the 52 panels per side symbolizing the 52 weeks in the year and/or the 52 years in the Half Venus Cycle (Calendar Round) are original features, or whether like the “91 steps” they may be another modern invention intended to entice tourism, a question that I’m not sure even a stunning collection of photographs like this can answer, but if I am to aspire to ever getting a real answer to that question, this book would still be the best place I can think of to start.

The Pyramidion Problem

I think the question of truly reconstructing the Great Pyramid’s capstone with the help of classical Greek authors has washed up on the rocks once again.

I am slowly realizing that certain remarks attributed to Diodorus Siculus concerning the pyramidion may be a misunderstanding. Unlike the case with Stecchini, where mis-attributed remarks at least seem to have some basis in Stecchini’s own formidable scholarship, the ongoing inability to trace the pyramidion quotes back to classic Greek and Roman sources suggests that they may actually be little more than another academic fantasy, and worse I’m still having the same difficulty tracing related remarks attributed to Pliny.

The real treasure that may have been unearthed in the latest search is that Lepsius may still have genuinely given us what we need in order to partly reconstruct the capstone of Chephren’s pyramid.

Blowing the Lid Off It

It should likely be filed under “too soon to tell”, since 48 hjours ago I had the image associated with the wrong individual, but as of late there has been renewed discussion of the coffers of the Saqqara Serapeum and the alleged technical precision of them, which has already managed to cover a lot of ground, including the topic of whether the ancients were able to soften stone for their purposes.

For some time I’ve been rather skeptical that the geopolymer methods of Davidovitz are really any way to go about building a pyramid, but it’s starting to sink in that this by no means indicates that stone softening techniques weren’t perfectly suitable for lighter tasks, even some involving the fitting of Megalithic components. Davidovitz’s contentions also seem to be generally compatible with the way we can view the problem from botanical perspective.

These latest discussions have also gotten as far as at least brushing up against the subject of whether stone softening techniques may have been used in ancient metals extraction, and whether they might play a role in any anomalous metallurgy.

In spite of any lack of industrialization in the modern sense, there may have been ancient advances in chemistry, electrochemistry, and materials science that may run parallel to some of the ancient advances in mathematics. (There doesn’t seem to be much room for debating that ancient South Americans didn’t know how to electroplate metals – even the normally reticent National Geographic was saying so, more years ago than I’d like to mention).

At any rate, the discussion of the Serapeum boxes not only attempts to put sarcophagi back on the radar screen, which they tend to fall off of because of some inherent ongoing metrological uncertainties, but the subject also conjures discussion of remarkable feats of stonework like the Elephantine naos, an artifact for which I am still searching for data for (and for any of its kind), because one of the most striking things about the Elephantine naos is that its top is in the shape of a pyramid.

The Elephantine naos, frequently referred to as a “granite box”.

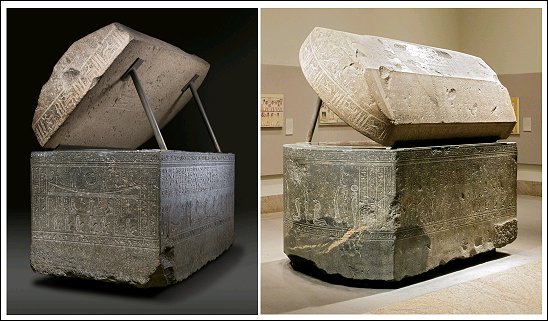

The similarity to this naos at the Temple of Horus in Edfu is often mentioned.

Even though its scale is much more on the order of a pyramidion than a pyramid, somehow I doubt that any ancient designer would have let such an opportunity go to waste, so that the proportions of such naos adornments as these pyramidal tops might be just as interesting as those of any pyramids or their capstones.

As I returned to work on some reference pages devoted to such subjects as the Elephantine box, whether we want to see it as a naos or a coffer, I was reminded of a very striking sarcophagus that I found apparently mis-attributed to Nesisut. With some further research, the correct attribution seems to be Wereshnefer, and there is a coffer attributed to Wennefer with some similar features as well, that also seems to merit attention.

The Metropolitan Museum has pages devoted to both of these two objects, along with some scraps of unattributed data. Dieter Arnold is listed as a source, but I’m finding it more or less impossible to get a look at the publication cited.

(Arnold, Dieter 1997. “The Late Period Tombs of Hor-khebit, Wennefer and Wereshnefer at Saqqara.” InÉtudes sur l’Ancien Empire et la nécropole de Saqqâra dédiées à Jean-Philippe Lauer. Montpellier: Université. Paul Valéry – Montpellier III, pp. 36–8; 51–4, figs. 13–6).

Coffer of Wereshnefer (30th Dynasty), Metropolitan Museum

Coffer of Wennefer (30th Dynasty), Metropolitan Museum

The beveling and other unusual features of the coffers seem to promise some unusual mathematics and metrology, even though the datasets are incomplete.

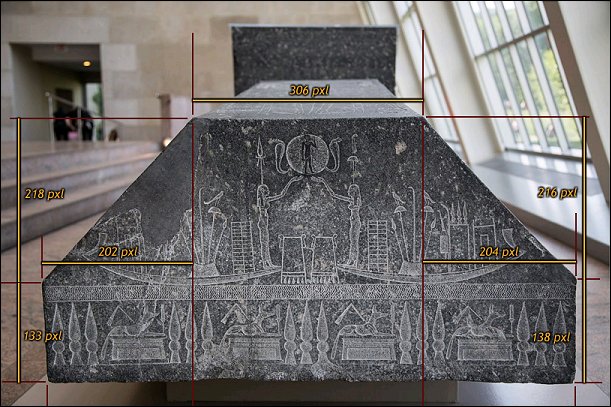

I have some work to do over, since I started experimenting with some pixel measurements of a photo that didn’t make for the best starting material because of a lack of geometric correctness. Thankfully the Metropolitan Museum’s photo collection includes one that may be more suitable for trying to piece together more of the coffer’s original proportions. Below you can see what I’ve done with it.

Rough pixel measures of the lid of Wereshnefer’s coffer, courtesy of Metropolitan Museum photo.

The data provided by the Metropolitan Museum reads as follows:

Wereshnefer: Dimensions: Box: L. 292 × W. at foot end 155 cm (9 ft. 6 15/16 in. × 61 in.); Lid: L. 292 × W. at foot end 155 × H. at foot end 81 cm (9 ft. 6 15/16 in. × 61 in. × 31 7/8 in.); Total H.: 211 cm (83 1/16 in.)

Wennefer: Dimensions: Box: L. 258 × W. at head end 150 × H. 113 cm (8 ft. 5 9/16 in. × 59 1/16 in. × 44 1/2 in.); Lid: L. 258 × W. at foot end 151 × H. at head end 49 cm (8 ft. 5 9/16 in. × 59 7/16 in. × 19 5/16 in.)

Something I found especially interesting so far is that for Wereshnefer’s coffer, the total height is given as 211 cm while the height at the foot end is given as 81 cm. It should be then given the data that the total height of just the coffer should be 211 – 81 = 130 cm.

211 cm = 6.922572178 ft, 81 cm = 2.657480315 ft, 130 cm = 4.265091864 ft

Does 6.922572178 remind anyone else just a bit of the Metonic Cycle of 6939.688?

81 cm = 2.657480315 ft; 10.67438159 / 4 = 2.668595398 ft = 81.3388 cm; 130 cm = 4.265091864 ft; 1.067438159 x 4 = 4.269752636 ft = 130.142 cm.

4.269752636 + 2.668595398 = 6.938348034 = 6939.688 / 1000 = 6.939688 to an accuracy of .9998.

If that’s any indication, what it very much looks like is not only that Egyptian designers were still using the Hashimi Cubit as late as Egypts’ 30th Dynasty, but were making as skillful use as ever of it in order to express important astronomical cycles at the customary days:feet ratio, astronomical cycles also being most likely the ultimate meaning of the hieroglyphs, symbols and designs that Wereshnefer’s coffer is covered in.

Also featured is the mathematical symmetry of x times 4 and (10) x divided by 4, very similar to the mathematica symmetry proposed for the base of the El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza from earlier in this post, and other ancient American sites.

Plus ca change…

Ancient Pillars of India

The recent discussions of the Serapeum that are headed for the subject of ancient metals technology also bring up a well-known example of anomalous metallurgy in the form of the Delhi Pillar and any other related examples (one of which is sometimes referred to as a Pillar of Ashoka). What caught the attention of Chariots of the Gods author Erich von Daniken and numerous other authors who followed in the same vein is the uncanny rust resistance of this iron pillar.

There is a GHMB thread on the subject that is about 20 years old now, but in general, searches turned up surprisingly little in the way of prior discussions.

I’m actually rather impressed with Wikipedia’s coverage of the Delhi Pillar and their extensive list of sources. Materials scientist R. Balasubramaniam has apparently written a number of things on the subject, including a book. Balasubramaniam may well have taken much of the mystery out of the Delhi Pillar in terms of material science, but it continues to haunt me just a tiny bit just how sophisticated this ancient artifact or others like it nonetheless often seems.

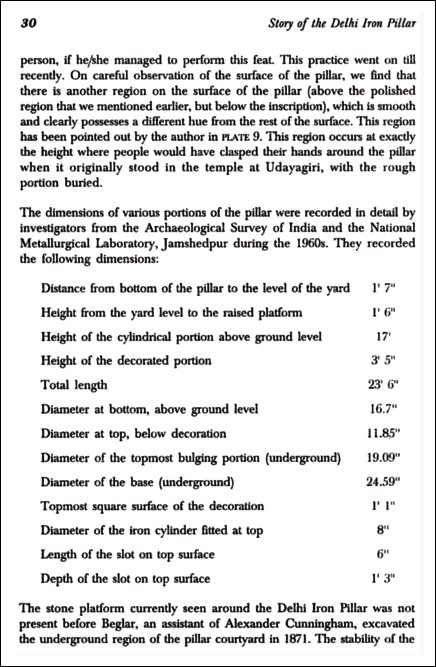

An unexpected benefit of spending a few hours having a look at the subject again is the finding of what may be reliable measurements even though there may be some general disparity between different sources boasting a knowledge of the iron pillar’s proportions. Google Books has a preview of Balasubramaniam’s book, Story of the Delhi Iron Pillar, where on page 30 appear a set of measurements attributed to the Archaeological Survey of India and the National Metallurgical Laboratory, Jamshedpur in the 1960s.

Sadly, although Balasubramaniam has made some of what look like his own contributions to the database on the metrics of the Delhi Pillar, his description of the missing capital of the pillar is so speculative as to seemingly constitute little more than a fantasy, and his descriptions in general suffer from being labelled with the angulam as the unit. Descriptions of the size an angulam tend to give values so variable it must at least border on the impossible to try to make sense of the measurements he gives.

Thankfully the older measurements he quotes seem as if they may be much more reliable, and while I have yet to undertake an extensive study of them, an initial study suggests the very same thing as with other studies of other things, that what we see isn’t a single metrology in use, but a surprising variety of different measurements systems being used in the design of a single object.

The older dataset that Balasubramanian cites also shows some rather interesting proportions between the parts, proportions that seem notably different than those of the extremely simple models that Balasubramaniam puts forward.

So hopefully more good things are in progress, but it’s been a slow week for as time-consuming as it is to hunt down new data, usually in vain. To be honest, most of the usable data I have from the last week was found by accident rather than through the many searches I’ve been running.

–Luke Piwalker